The hostilities of the Mexican-American War concluded in 1848 with the ratification of the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo. This event marked the beginning of the long process of integrating both the new territories of the Mexican Cession and their former Mexican citizens into the U.S. political and legal framework. As part of the peace treaty, the U.S. agreed to honor property rights of Mexican citizens established prior to the war. But, titles granted to individuals, families and communities were formed under a distinctly different legal system, were much larger than traditional U.S. land grants and had boundaries that were often not clearly identifiable. These issues quickly placed Mexican land owners into direct confrontation with land hungry American settlers moving to the new territories. The inevitable conflict between these two groups was disputed in both state and federal courts over the next several decades and continues into the 21st Century[1].

Despite many similarities, the successful retention of property by land grant claimants in California was markedly better when compared to land owners in New Mexico. 76% of claims in California were successful and adjudicated quickly. California confirmed 618 claims out of 813 brought into adjudication by 1856.[2] In stark contrast, only 22% of claims in New Mexico were successful. New Mexico confirmed only 46 claims out of 205 brought into adjudication by 1886. They slowly, inefficiently and inconsistently continued to adjudicate hundreds more claims into the 20th Century. [3] This disparity is briefly observed and dismissed by both Malcolm Ebright and Phillip B. Gonzales who independently conclude that “the population increase due to the Gold Rush made land more valuable, and statehood gave California more leverage in Washington than was enjoyed by New Mexico.”[4] While this certainly explains why claims issues were resolved quickly in California, it does not explain why the results were so favorable to many former Mexican citizens of California when compared to former Mexican citizens of New Mexico. Howard Lamar argues that New Mexico was unique because instead of a “flood tide of American settlers overwhelming the system… the attempt to impose American land customs was made by a minority of Americans in a predominantly Spanish-Mexican population.”[5] But, this fact would indicate that Mexican citizens had a larger advantage than their counterparts in California. So the question remains, why were land grant claims more successful in California than they were in New Mexico?

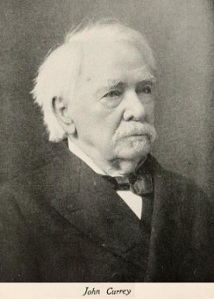

When taking into account the actions and goals of a majority of California citizens regarding Mexican land grants, the positive outcome of grant holders is even more perplexing. John Currey, a lawyer who represented many Mexican land grant claimants explained the political situation in 1850s California in his memoirs where he stated:

The squatters of the State constituted a formidable portion of the citizens of the State,whose powers as electors won over to their side of the controversy with the owners of Mexican land grants many ambitious politicians of low civic morality. They elected candidates to the legislature and thus secured passage of laws supposed to be for their benefit and advantage, but which in the end proved to be of no advantage or benefit to them. Our Supreme Court during the period of Squatter domination, by their decisions, maintained the law, and thus secured to owners of Spanish Land titles, their lands.[6]

The different interpretations of individual land grant claims that led to the large disparity in outcomes between California and New Mexico can only be explained by the highly influential cohesion of class in the territories of the Mexican Cession despite a highly racialized atmosphere. In both New Mexico and California, claimants were made up of affluent and non-affluent Mexicans, affluent and non-affluent Native Americans, affluent Anglo-Americans who purchased grants from grantees before and after the war, and non-affluent Anglo-Americans moving to the territories after the war. Both general statistical totals and individual cases show that class had an overwhelmingly significant role in the outcome of land grant cases. California claims were more successful purely due to the fact that most of the claims were originated by affluent people who happened to be either Mexican or American. New Mexico claims were less successful due to the fact that most of the claims were made by less affluent people who happened to be Mexican.

[1] Malcolm Ebright. Land Grants and Lawsuits in Northern New Mexico (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1994), pp. 4-5.

[2] R.H. Allen. “The Influence of Spanish and Mexican Land Grants on California Agriculture.” Journal of Farm Economics (Oct 1932), p. 679.

[3] Phillip Gonzales. “Struggle for Survival: The Hispanic Land Grants of New Mexico, 1848-2001.” Agricultural History (Spring 2003), p. 303

[4] Ebright, p. 33

[5] Howard Lamar. “Land Poicy in the Spanish Southwest, 1846-1891: A Study in Contrasts.” The Journal of Economic History (Dec 1962), p. 498

[6] Judge John Currey Memoir. Transcribed by Wyman Riley (Nov 1958), p. 4.